On 23 August 1966, Gurindji Elder Vincent Lingiari led more than 200 Indigenous workers and their families in a walk-off from Wave Hill cattle station, sparking one of the most powerful land rights movements in Australian history.

It was a landmark act of protest, serving as a reminder today of what is possible when we stand together in the pursuit of justice. What began as a demand for fair pay and decent conditions quickly became a call for justice, sovereignty and the return of stolen land.

“We want to live on our land, our way.”

Vincent Lingiari

Why did the walk off happen?

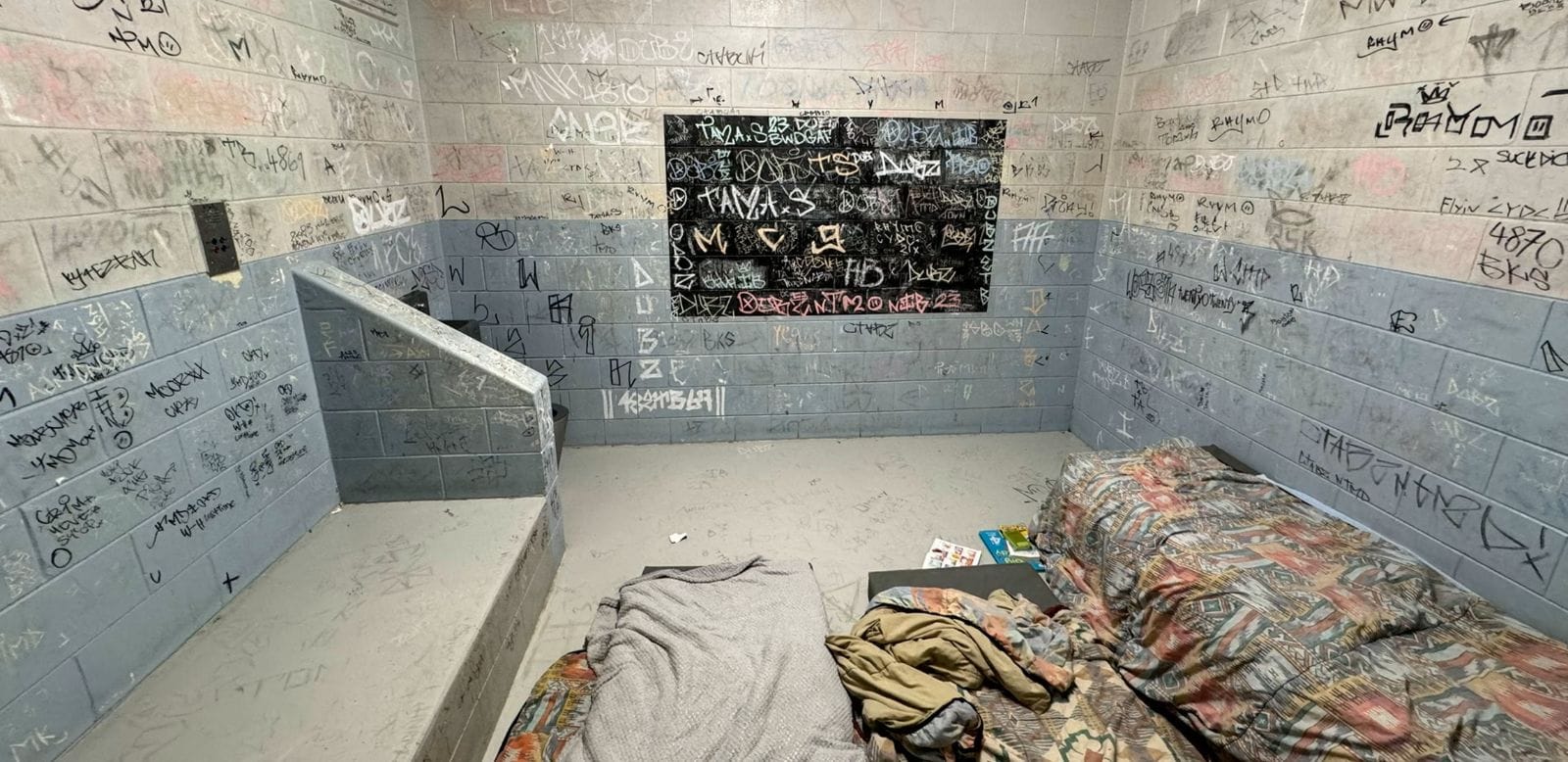

On 23 August 1966, Gurindji Elder and union leader, Vincent Lingiari, led more than 200 Aboriginal stock workers and their families off the Wave Hill cattle station in the Northern Territory. They were subjected to ongoing discrimination, employed under harsh, unequal conditions, paid poorly or not at all, and forced to live in overcrowded, unsafe housing.

The walk-off began as a demand for fair wages and better working conditions, but the Gurindji people were also demanding the return of some of their traditional lands, which had been taken when the British meat-packing company Vestey Brothers bought Wave Hill Station in 1914.

“You can keep your gold. We just want our land back,”

Vincent Lingiari

A land rights movement

After the walk-off, the Gurindji people relocated to Wattle Creek and established the community of Daguragu where they built a new settlement and launched a campaign to reclaim ownership of their land.

Their message was clear: this was not just about jobs – it was about cultural survival and the right to live on their own Country, under their own laws and customs.

For years, the Gurindji community campaigned tirelessly, travelling around Australia bringing attention to their fight, and petitioning the Governor-General for ownership of their Country.

With increasing support from unions, churches, activists and the Australian public, their campaign helped shift national awareness about the lasting impacts of dispossession and the importance of land rights for First Nations peoples.

A powerful moment of justice

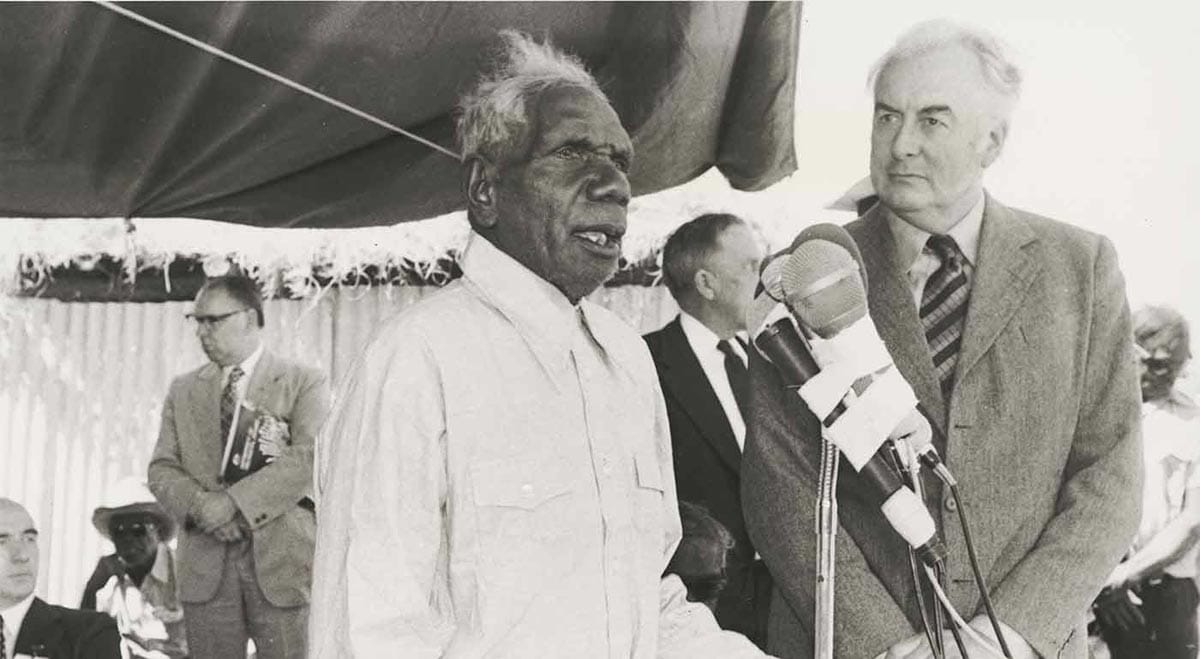

In 1973, nearly nine years after the walk-off began, Prime Minister Gough Whitlam authorised funds to support the purchase of part of Wave Hill, marking a critical step toward recognising Aboriginal land rights.

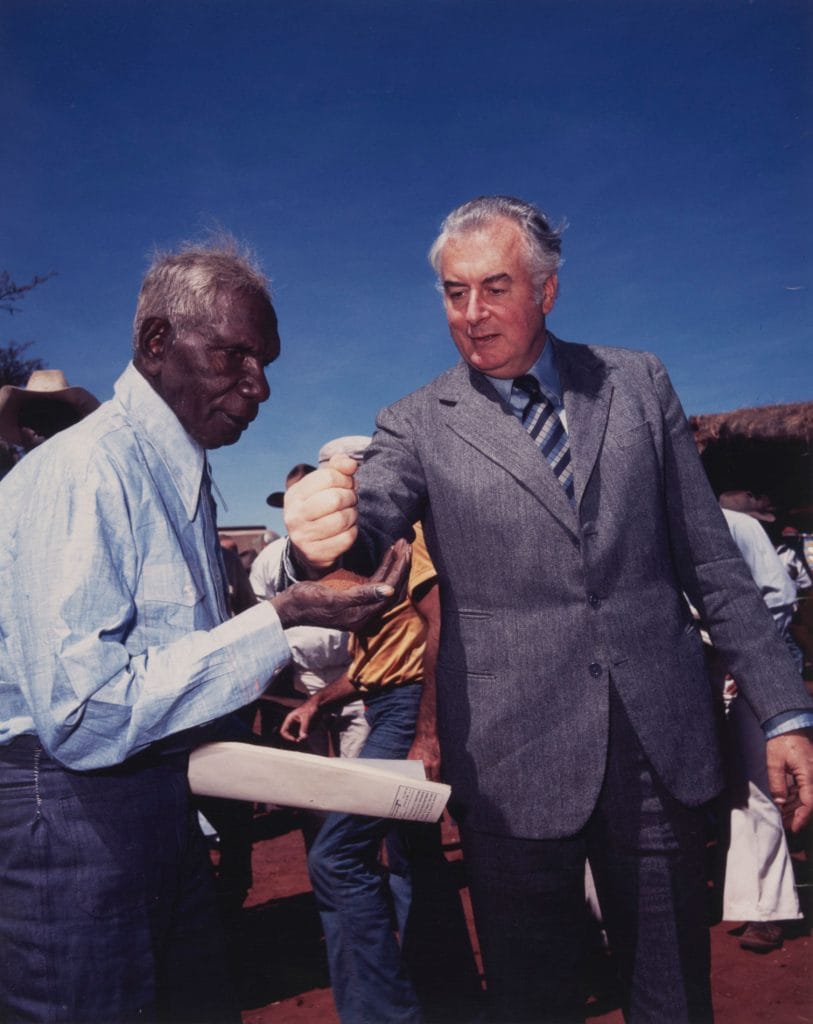

Following this, the Vestey company agreed to hand back a portion of their land that was then secured by the Aboriginal Land Fund Commission. On 16 August 1975, Whitlam travelled to Daguragu to officially return it to the Gurindji people, pouring a handful of red earth into the hand of Vincent Lingiari in a symbolic act acknowledging the Gurindji community’s deep connection to their Country.

A year later, the handback played a pivotal role in the development of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976, the first law in Australia to recognise the rights of Indigenous people to reclaim land based on traditional ownership.

The power of protest

The Wave Hill Walk-Off is a vital part of Australia’s history that shows the power of peaceful protest, determination, and community leadership. It proved that when First Nations voices are heard, meaningful change is possible.

We know that the right to peacefully protest is constantly under threat in Australia.

In recent years, there has been a rise in the introduction of laws that attempt to limit the right to protest, and people’s ability to speak out against injustice; from heavy fines and penalties for protestors in NSW and QLD, to the unlawful surveillance of student protestors at the University of Melbourne and the increase of police powers to disperse crowns and prevent protests in Victoria.

This isn’t new. Throughout history, authorities have repeatedly tried to suppress resistance and Indigenous people have long been the target of efforts to silence their calls for justice – through police violence, legal restrictions and the criminalisation of protests.

But despite ongoing attempts to silence the fight for First Nations justice, the Wave Hill Walk-Off and the Gurindji people’s determination is an inspiring reminder that persistent protest, in this case more than seven years, can lead to historic change.

The legacy of the Wave Hill Walk-Off

The Wave Hill Walk-Off stands alongside other landmark actions led by First Nations peoples in the ongoing fight for land justice, like the Yolngu people’s presentation of the Yirrkala Bark Petitions in 1963, and Eddie Mabo’s historic legal challenge that led to the 1992 Mabo decision; reflecting generations of resistance, strength, and the deep connection of First Nations communities to their lands.

But the fight for First Nations justice is ongoing. Across the country, too many communities are still denied their rights to land, culture, and self-determination, despite decades of advocacy.

In the wake of the failed Voice to Parliament referendum, the legacy of the Wave Hill Walk Off is especially important in reminding us that change doesn’t always come quickly, but through determination and sustained action. Through our campaigns and advocacy, we will continue to stand with First Nations peoples in calling for land justice, truth, and the right to live on Country.

Change doesn’t happen overnight – but together, we’ll keep showing up and raising our voices until First Nations people’s right to land, justice and self-determination is upheld.

Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 10 million people who take injustice personally. We are campaigning for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all – and we can only do it with your support.

Act now or learn more about our Indigenous Justice campaigns.

Sources:

- Common Ground – The Ongoing Legacy of the Wave Hill Walk-Off

- SBS NITV – Explainer: What was the Gurindji Land Handback and what did it mean for Aboriginal land rights?

- Deadly Story – Gurindji strike for their land