Damisoa is from the Androy region in the very southern tip of Madagascar. In 2021, he and his family were forced to leave their home due to droughts worsened by climate change meaning there wasn’t enough food for them to survive there.

People displaced by famine and now living in northern Madagascar urgently need humanitarian assistance. But aid is currently almost exclusively concentrated in drought-stricken southern Madagascar.

Damisoa tells his story of displacement and survival and calls for the government to take urgent steps to address the hunger, homelessness and poor healthcare faced by him and others displaced by drought in Madagascar.

I should not have left my ancestral land, in southern Madagascar, but we were forced to leave. Famine had attacked our land.

I didn’t have much to sell to afford the journey: no goat or zebu (cattle), so we sold the cooking pots and the furniture from our home. That made us enough money for our family of 10 to leave. But it didn’t get us far.

We stopped in Toliaria and then again in Antananarivo. Each time, finding whatever work we could to raise the money for the next bus fare: gem mining, menial work, cleaning and laundry. The whole family, including my wife and my children, worked hard to raise money.

Eventually we made it to Ambondromamy, in the Boeny region, in northern Madagasacar. We were told we could earn a living in the forest by burning charcoal and growing corn and mung beans. Straight away, we began cultivating our crops and producing charcoal.

Then the authorities came. As newcomers, we were afraid: when we saw their guns, we ran away. Some of us were arrested while others were left behind.

Now we have a place to stay, but we are still suffering

Eventually the local government found a solution for vulnerable people by resettling us to some small huts in Tsaramandroso, nearby. They built a place for people to stay. I did not bring my family this far for us to die, but to save our lives. So, we accepted the offer of a place to live.

However, when we were settled, we continued to struggle. The huts do not feel like we are sleeping indoors. Especially during the rainy season (every December to April), it feels like a thunderstorm inside: the walls let the rain in, and our space is flooded.

The water around us is deadly

When the water is high, during the rainy season each year, it kills people. This water has a monster and invisible creatures in it: the river is infested with crocodiles. It is also very fast flowing, and people have died trying to cross, so we are afraid of passing through until the tide is lower.

We do not have a boat to cross the river, we use yellow jerry cans as an alternative. We attach the jerry cans with a long rope on the other side of the water and pull it across. We are never sure if it will break or not. Several people help: some know how to swim and can help others cross by carrying them on their backs.

When there is no more to share, we sleep hungry

We do not have any seeds or food to eat. Because of this poverty, we ignore the danger, and we try to cross the water because we need to look for food. I feel like we live in an abyss, not on earth. Where can we go when we have this water around us?

We would die if we did not help each other. Whenever one of us, from among the 33 households, has something we share it. When there is no more to share, we sleep hungry. We take lalanda leaves (wild sweet potato leaves), boil them with water and salt, and that is what we eat to survive until the next day.

We are fearful of getting sick

My sister went into labour during the rainy season, when the water was high. We did not have enough money to bring her to the doctor. Instead, we walked three hours, crossing the deadly river to see the matron.

Sadly, my newborn niece died because her mother, weakened by hunger and thirst, could no longer breastfeed.

We are fearful of falling sick because we do not have any health insurance. We are poor, so we are careful to avoid complications.

We would only struggle more if we moved elsewhere

We stay here in the North, because we struggled more when we were back in our ancestral land, in the South. And if we leave this place, we will face more struggles. If we leave again, we will be displaced again to a new place, alone, with no government support or humanitarian aid.

We would rather suffer here. It is better to stay with people you are acquainted with. And the land we are staying on is the only place the government has made available for people in our situation.

So, we prefer to stay, but we struggle. We do not have a plough to till the land, we do not have oxen. But we stay here to avoid more struggle.

I am not ashamed to demand humanity

As the head of the village, I represent the residents here. It’s important to me that I do them justice in this role and use this position to amplify my community’s voices. We are not ashamed of our poverty which is due to the lack of government support given to us.

We are not ashamed to talk about our struggles. There is nothing to hide. If we let shame stop us from speaking out, all of our people could die.

This is where we live, this is our situation. We ask the government to consider our request for support. We look forward to their assistance.

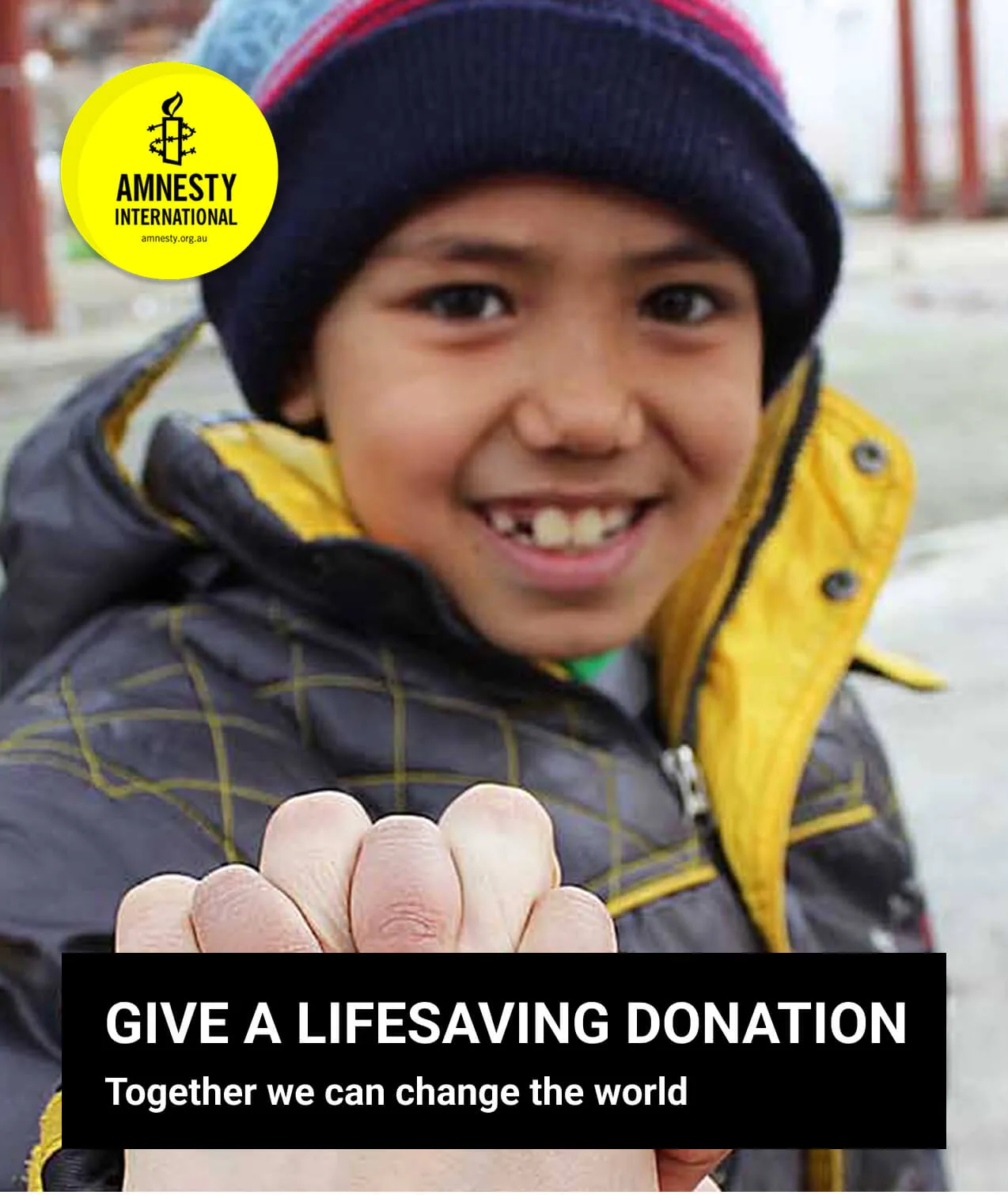

Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 10 million people who take injustice personally. We are campaigning for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all – and we can only do it with your support.

Act now or learn more about our human rights work.