Cyrille Traoré Ndembi, 61, is the President of the Vindoulou Residents’ Collective, a neighbourhood on the outskirts of Pointe-Noire in the Republic of Congo. This retired community development specialist has been fighting to defend the residents’ right to a healthy environment since he moved there in 2019.

His house is located just ten metres from the Metssa Congo plant run by a subsidiary of the India-based Metssa Group. This recycling plant produced lead bars for export from 2013 to 2024, 50 metres from a school and in the middle of a residential area. Cyrille noticed severe health problems in his family including respiratory and digestive disorders. Blood tests on some residents showed lead levels far above the alert level set by the WHO.

Following Cyrille’s campaigning, and with the help of Amnesty International, the authorities ordered the plant’s closure in December 2024. Cyrille continues to fight for justice for his community.

“When I arrived in Vindoulou, I quickly realized the danger we were in. The air was unbreathable!

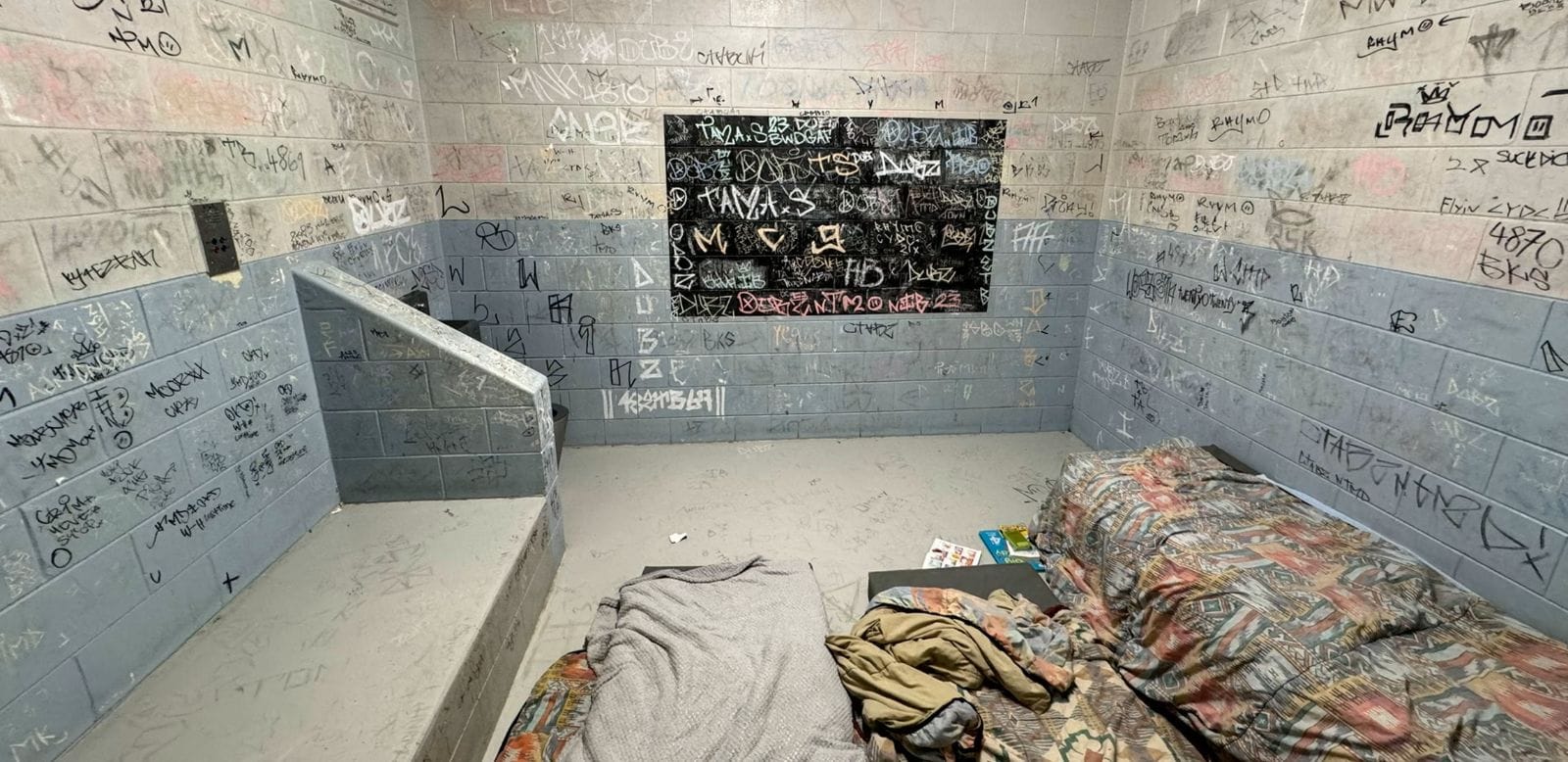

Black dust and fumes were spreading and invading our homes. Sometimes, when we went out, we couldn’t even see our nearest neighbour. The plant staff discharged oil and wastewater in front of our houses. Metal debris from the plant’s chimney fell onto our roofs. Once, I went to walk along the wall of the plant and debris fell on me like hail.

Right from the start, I had doubts about the legality of this activity in the middle of a populated area. I couldn’t understand how a substance as dangerous as lead could be recycled using processes that were, in my view, contrary to the standards and regulations in force.

‘My whole family was ill’

We arrived in Vindoulou in August 2019 and by January 2020 my whole family was ill. Our children were found to have the beginnings of pneumonia, bronchitis and bronchopneumonia. We also had diarrhoea and abdominal pains.

Across the neighbourhood, people had the same problems. I was told that the children who had moved away from Vindoulou no longer suffered from those symptoms.

The residents believed that nothing could make this company leave. For the community, it was David against Goliath. Some even called me King David.

I went door-to-door to convince people that something serious was going on. Everywhere I went, I reminded people of article 41 of our Constitution: every citizen has the right to live in a healthy environment.

I explained to people the benefits of getting organized together and taking up the fight. Today, our collective has over a hundred members.

From survivor to human rights defender

We tried to meet the directors of Metssa Congo. We met the plant’s manager, who said he was not authorized to comment on the subject. He promised us an audience with the CEO, but it never took place. They wouldn’t talk to us, simply saying that they had authorization to operate. We couldn’t even consult their environmental impact report, which is a document that we were entitled to access under the current legislation. After calling in a bailiff, I was finally able to consult another type of document, their environmental audit report produced after they had already begun operations.

In 2022, I went to meet Amnesty International’s representatives to alert them. From 2023 onwards, Amnesty investigated and provided funds to carry out blood tests on a sample of the population. We then had proof that people tested had high levels of lead in their blood.

I took two blood tests, in March and September 2023. They showed blood lead levels above 400 µg/L. For the 17 other people tested, the levels were alarming. When the ministry carried out other tests in 2024, some ex-workers had levels of 1,000 µg/L – that’s enormous!

My youngest daughter just turned four. Of the nine children tested, she had the highest lead level, above 530 µg/L. I’m worried about her. She’s running fevers even though she has no infection.

Amnesty also helped us take legal action in 2023, to publicize our situation and, in the face of the administration’s inaction, to make a plea to the authorities. As a result, the minister [of Environment] came here and spoke to the population in December 2024. We as a collective did not have a formal audience with the minister. The authorities received Metssa Congo’s managers for an audience in Brazzaville [the Republic of Congo’s capital] several times, but never our collective! I’m not being heard. Ideally, we should be able to talk directly to the authorities.

Facing intimidation

I’ve been under pressure. Metssa filed a complaint against me alleging defamation in May 2024. I went to court, but Metssa didn’t show up. They were bolstered by the decision of the Supreme Court’s public prosecutor that allowed them to resume their activities after a suspension ordered by an administrative judge in April 2024.

One night, some young people came and threatened me. It was stressful, but I didn’t back down. At the time, the workers were against what I was doing. Now, most of them have joined us in our fight.

When the company’s operations were suspended again in June 2024 by the Ministry of Environment, we continued to fight because the word suspension meant nothing to us. We wanted to hear the word closure. When the decision was taken on 11 December 2024 to close and dismantle the plant, we were relieved, but the fight was far from over.

We are worried the soil may be contaminated. There may be a risk of groundwater contamination, and we drink the water from the borehole. The Ministry of Environment has taken samples, but we have not been made aware of the results.

Today, we need to know how many people are ill. People need to be screened, treated and moved out of harm’s way. In July, the Ministry of Health announced that it would conduct blood tests on an additional 100 people. It still hasn’t been done; we haven’t heard anything.

Things are moving too slowly. Why not carry out systematic screening of all those who may have been exposed? There are far more than 100 of us. Since the minister of Environment’s visit, people are worried. Some wanted their entire families screened.

The most important thing is people’s health. I fight to save lives. I’d like to set up an NGO to defend the environment beyond Vindoulou. We’re not the only ones in these situations. Anyone who can help communities in difficulty, now is the time to take action, because sometimes those communities have no recourse and are left to fend for themselves. We have to join hands. It won’t fall from the sky. It’s up to citizens to fight.”

Before setting up the plant in 2013, Metssa Congo had not carried out an environmental impact assessment, in violation of Congolese law. Despite this, the Ministry of Industry permitted Metssa to operate. The company claimed to have obtained an operating licence in 2018 and a certificate of compliance in 2023, and claimed that the emissions from the plant were not toxic.

Following the publication of Amnesty’s report on the state’s failure to protect the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment in Congo including in Vindoulou, the authorities decided to suspend Metssa Congo’s operations on 17 June 2024, and launched a technical investigation by the Ministry of Environment on 8 August 2024. The plant began being dismantled on 19 December 2024 with the removing of the roof and some furnaces by Metssa Congo, but the process stopped before completion.

The government ordered Metssa Congo to set up a solidarity fund, but this has yet to materialize, according to Cyrille Traoré Ndembi. The residents of Vindoulou continue to claim for compensation after 10 years of exposure to lead.

Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 10 million people who take injustice personally. We are campaigning for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all – and we can only do it with your support.

Act now or learn more about our human rights work.