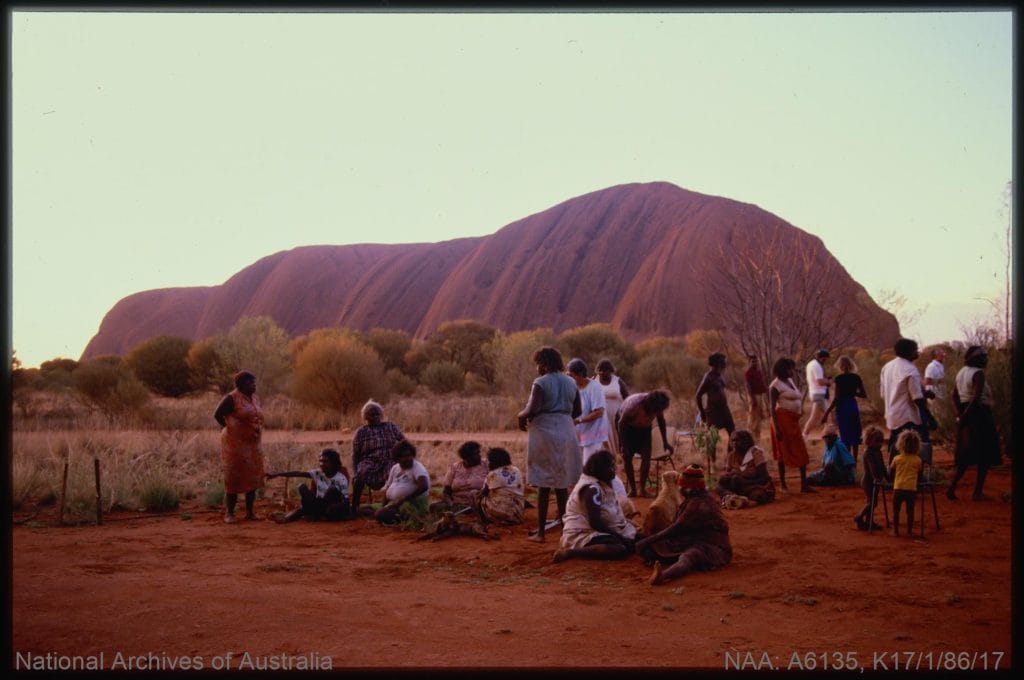

This year marks 40 years since the formal return of Uluru Kata Tjuṯa National Park to the Anangu Traditional Owners. It was a moment of recognition that followed more than a century of dispossession and decades of the Anangu peoples sustained resistance, advocacy and fight for justice.

Anangu: Traditional Custodians of Uluru and Kata Tjuṯa

For thousands of years before the invasion of Australia, the Anangu people have been the Custodians of Uluru and the surrounding lands of Kata Tjuṯa. In their tradition of Tjukurpa, the belief system that guides every aspect of Anangu life, the care and protection of the lands of Uluru and Kata Tjuṯa are sacred responsibilities.

Colonisation and tourism

In 1873, European explorer William Gosse became the first recorded visitor to Uluru, naming it ‘Ayers Rock’ after Sir Henry Ayers. In doing so, he erased from official maps what was already known and named by the Anangu people as Uluru.

By 1948, the first road was built in the area and two years after that in 1950, it was declared Ayers Rock National Park. Within 10 years, the area was renamed Ayers Rock–Mount Olga National Park, under the control of the Northern Territory Reserves Board, with the construction of an airstrip underway to accommodate increasing tourism.

In 1936, there was the first recorded recreational climb of Uluru. By 1966, a metal chain was installed on part of the route – extended in 1976 to support a rapidly growing numbers of climbers. These developments proceeded without the consent of the Anangu people, who had consistently made clear that climbing the rock was a violation of Tjukurpa.

Ongoing advocacy for rights

As tourism evolved, the Anangu people were restricted access by the government.

Despite this, they continued to press for change and return to Country for gathering, ceremony and responsibilities to care for the land, whilst consistently raising concerns about damage caused by mining, pastoralism, tourism and the desecration of sacred sites.

When the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act passed in 1976, it provided a process for First Nations people to claim land rights for Country where traditional ownership could be proven – but Uluru–Kata Tjuṯa was excluded. In 1977, the land was redeclared as Uluru (Ayers Rock–Mount Olga) National Park, under Commonwealth control, yet this did not grant back Anangu rights to own or manage it.

Years of activism followed, through legal claims, letters, meetings and sustained political pressure as the Anangu people maintained that responsibility for the land and its law could not be separated.

The handback

In 1983, it was announced that the Anangu people would reclaim claim ownership of the park following amendments to the Aboriginal Land Rights Act. On 26 October 1985, the title deeds for Uluru–Kata Tjuṯa National Park were formally returned to the Traditional Owners, legally recognising of their preexisting rights.

That same day, the Anangu signed a 99-year lease with the Australian National Parks and Wildlife Service (now Parks Australia), establishing joint management of the park with a majority of Anangu members.

Since the handback, the park has been recognised by UNESCO for both its natural and cultural significance. A Cultural Centre opened in 1995, and during the 2000 Sydney Olympics, the flame was carried through the park by Anangu Traditional Owners.

Despite their objections, climbing Uluru continued for decades causing irreparable environmental damage and resulting in at least 37 deaths. In 2019, 34 years after the handback, the climb was finally closed.

Today, the park remains under joint management. But land rights alone aren’t enough.

True justice means ongoing respect for Anangu culture, law, and self-determination. This anniversary marks a long struggle for land rights, recognition and justice. For the Anangu people and many First Nations communities, the fight to protect Country and culture is ongoing. Recognition alone is not enough – real justice means backing Indigenous-led efforts to X and defending the right to self-determination.

Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 10 million people who take injustice personally. We are campaigning for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all – and we can only do it with your support.

Act now or learn more about our Indigenous Justice campaigns.