In this guide, we break down five common terms used in the justice system to give you a clear picture of how they function and the impact they have on those caught within cycles of incarceration.

Remand

Remand refers to alleged offenders who are held in custody before and during their trial (on criminal charges) by order of a court. They are unsentenced and innocent until proven guilty.

- Prisoners on remand now make up 42% of Australia’s prison population.¹ They also tend not to have access to meaningful programs or services while incarcerated.

- The growing reliance on extended periods of remand – often for minor offences – damages lives, relationships and future prospects. In 2023, 32% of unsentenced people in Victorian prisons were held on remand for more than six months, and 17% for longer than a year.²

- Many people who spend time on remand are found not guilty or have the case against them withdrawn. Data from NSW shows that many remand prisoners serve more time on remand than they would have spent in custody were they to be sentenced, especially with increasingly congested courts.³

- On an average day in 2023-24, the proportion of children ages 10 to 17 in Australian detention facilities who were unsentenced was 80% – 4 in 5 detained children.⁴

Watch houses

Police watch houses are buildings designed “for the temporary holding of prisoners before prisoners are released or transferred to a corrective services facility or detention centre”.⁵ They may also be used to hold people who are intoxicated, appear mentally ill, or are awaiting trial.

- Watch houses are also referred to as police cells, station cells, lockups, holding cells, jails, and custody suites.

- “Temporary” can mean a period as long as 4 weeks.⁶

- The Northern Territory’s Ombudsman has labelled watch house facilities “inhumane“.

- The Queensland government won’t set a maximum limit for how long a child can be held in a watch house. In 2025, a review found children were spending an average of 161 hours (6.7 days) in the state’s watch houses.⁷

Spit hood

A spit hood is a mesh face covering – sometimes known as a safety hood or anti-spit guard – that police and correctional officers place over a person’s head to prevent themselves being spat on.

The non-permeable piece of material near the wearer’s mouth makes breathing more difficult, and there have been multiple deaths in custody across Australia in incidents associated with spit hoods.

“The use of spit hoods with children as young as 10 years of age is completely unacceptable and a breach of the human rights of children under the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, to which Australia is a signatory.”

Australia’s National Children’s Commissioner, Anne Hollonds

Solitary confinement

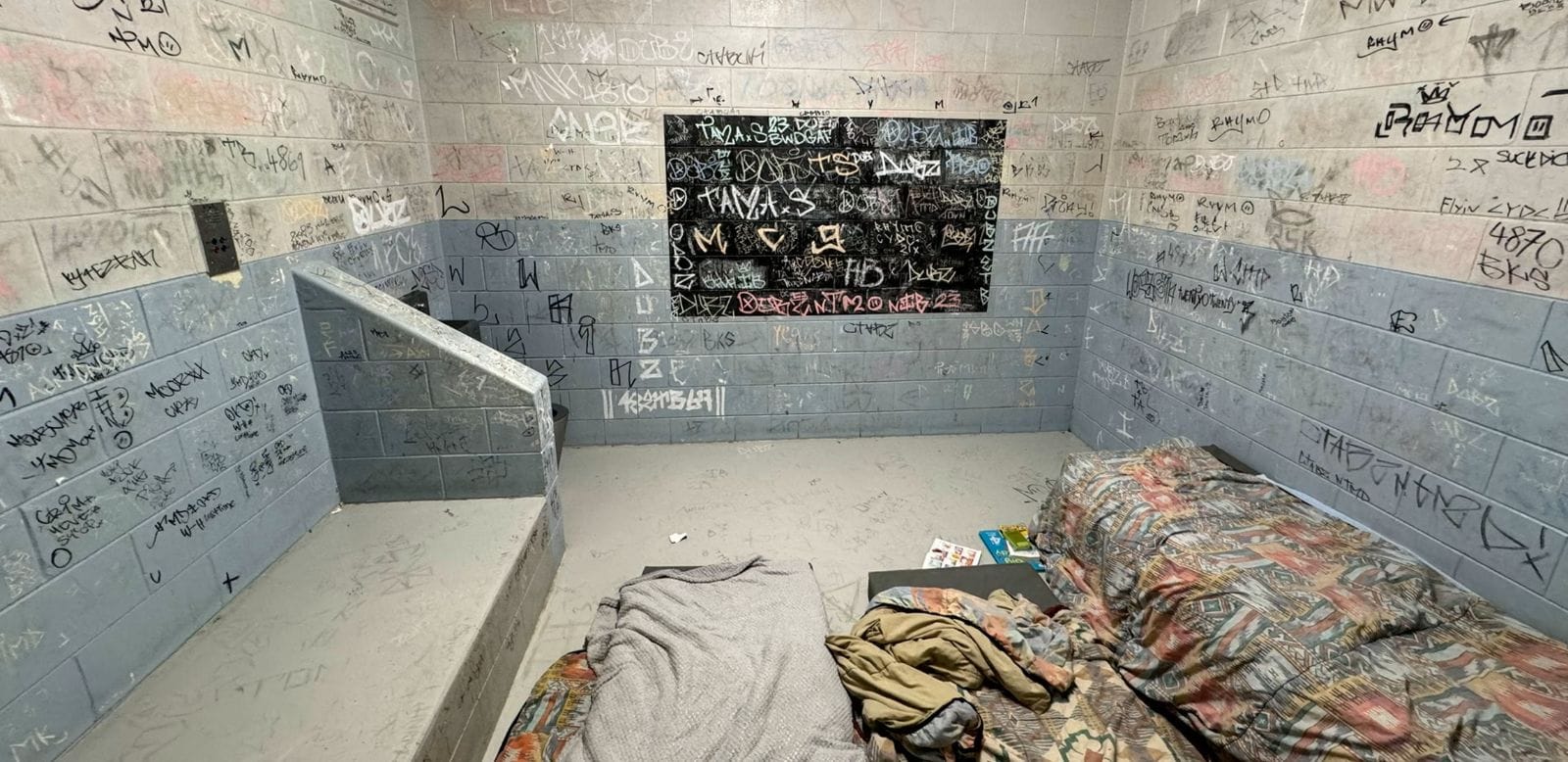

Solitary confinement is a harmful practice of physical and sensory isolation that exists in all Australian states and territories by many different names: isolation, separation, seclusion, segregation and lockdown.

It is the confinement of prisoners for 22 hours or more per day without meaningful human contact.⁸

These extended hours of isolation are usually spent in small, concrete cells with limited ventilation and natural light. Most contact with prison and health staff is perfunctory and may be wordless, and access to reading or educational materials is often denied.

An indicative example: The use of solitary confinement increased in South Australia’s only children’s prison by 50% in 2024 ⁹ where the majority of imprisoned children are Indigenous (55% in 2023-24).¹⁰

Diversionary programs

Diversionary programs are initiatives designed to redirect individuals, particularly children and young people, away from the criminal justice system.

They aim to provide rehabilitative alternatives to traditional methods of punishment in order to address the underlying issues leading to offending behaviour.

- Diversionary programs are effective. Only 1 in 5 people who receive a diversion plan are sentenced for other offending at some stage in the next 5 years (21%). In comparison, almost twice as many people who receive other court outcomes are sentenced for other offending in the next 5 years (40%).¹¹

- The first challenge is to ensure young people have something meaningful to be diverted towards. The other is “everyday racism among public officials which discriminates against First Nations children”.¹²

- There is a significant body of Australian research that shows the adverse use of police discretion in relation to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people: they are less likely to receive a police diversionary option and are more likely to be arrested, to have bail refused and to have their matter determined in a youth court when compared with their non-Indigenous peers.¹³

- Despite the gross over-imprisonment of First Nations children correlating with ongoing colonisation, racism and destruction of their communities¹⁴, there are “limited programs and diversionary alternatives specifically for Indigenous young people, particularly in rural and remote communities, and diversion programs that do exist are often Eurocentric in nature”.¹⁵

²Children’s Imprisonment in Australia 2024 | Justice Reform Initiative

³Locking up kids has serious mental health impacts and contributes to further reoffending | UWA

⁴United Nations Rules for the Protection of Juveniles Deprived of their Liberty | OHCHR

⁵Recorded Crime – Offenders, 2023-24 financial year | Australian Bureau of Statistics

⁶Is Australia in a youth crime crisis? Here’s what the numbers say | The Conversation

⁷Youth justice in Australia 2023–24, Summary – Australian Institute of Health and Welfare

⁸The social determinants of justice: 8 factors that increase your risk of imprisonment | UNSW

¹²Justice reinvestment in Australia | AIC

¹⁴Explainer: Solitary Confinement of people in prison – Human Rights Law Centre

Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 10 million people who take injustice personally. We are campaigning for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all – and we can only do it with your support.

Act now or learn more about our human rights work.