As Australia heads into an election year and steps up its bid for a UN Human Rights Council seat, now is the time to show human rights leadership. Yet, Australia is missing the chance to be a world leader on human rights due to its failures on Indigenous and refugee rights and new draconian laws. Read our Annual Report for 2015/16 and find out how our leaders can make the most of this opportunity for change.

Global human rights trends

Our new report analyses global human rights trends over the past year in 160 countries. It finds that international protections of human rights are unravelling, as families flee spiralling conflict and repression, only to find wealthy countries shutting their doors. Short-term national self-interest and draconian security crackdowns have led to a wholesale assault on basic freedoms and rights.

In 2015 Australia was one of many that used ‘national security’ to justify undermining human rights and turn its back on vulnerable people.

Australia is condemned in the report for its dangerous refugee policies of offshore processing, mandatory detention and boat pushbacks, and soaring Indigenous imprisonment rates.

The report criticises repressive laws, including those allowing for the silencing of staff and contractors who reveal human rights violations in immigration detention and the stripping of dual nationals of citizenship without any criminal conviction.

Amnesty International Australia National Director Claire Mallinson said it was time for Australia to show consistent leadership:

“Our leaders have been saying one thing and doing another, and we cannot be convincing on human rights on the world stage while we try to hide our own abuses under the carpet.”

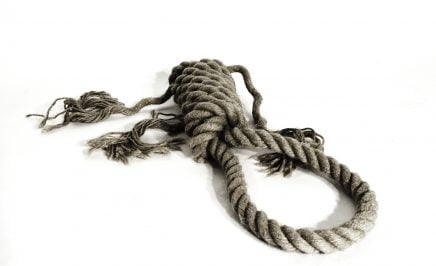

“Australia showed glimpses of global human rights leadership in 2015 by announcing the resettlement of 12,000 Syrian refugees and pledging to campaign for a worldwide end to the death penalty – but glimpses are not enough.

“It’s time for our leaders to turn words into action. We need leadership underpinned by our shared values of fairness, openness, human dignity, justice, and freedom.”

Australia must lift its refugee quota to at least 30,000 people in 2016 and end the regime of offshore detention. To reduce Indigenous imprisonment rates, the Federal Government needs to follow in the footsteps of Victoria, the ACT and the Northern Territory and set justice targets .

Refugees

2015 was the year little Alan Kurdi drowned on a Turkish beach, because governments sat on their hands instead of protecting people in Syria and giving them safe routes to flee. We can be better than this. We can be a strong Australia, willing to help people in their darkest hour.

Amnesty International Australia National Director Claire Mallinson

Over 60 million people are currently displaced and seeking refuge worldwide, more than at any point since World War II.

The past year severely tested the international system’s willingness to respond to crises and mass forced displacements of people – and found it woefully inadequate.

“2015 was the year little Alan Kurdi drowned on a Turkish beach, because governments sat on their hands instead of protecting people in Syria and giving them safe routes to flee,” said Claire Mallinson.

In 2015, Australia was one of more than 30 countries that illegally forced refugees to to return to countries where they would be in danger.

Successive Australian governments have pursued increasingly hard-line deterrent policies to block out people seeking asylum. The current government is still choosing to send children to Nauru, despite clear evidence of harsh living conditions, independent reviews highlighting abuse, and uncertainty driving people to self harm and attempted suicide.

“We can be better than this. We can be a strong Australia, willing to help people in their darkest hour. An Australia that is diverse, open and free, where all people have a right to live in dignity and raise their families in safety,” said Claire Mallinson.

“Our leaders need to work with neighbouring countries to assist people seeking asylum to find safe places where they can rebuild their lives. We need creative solutions that help people on the move, not deterrence policies that cause harm and put people of sight and out of mind.”

Indigenous rights

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people continued to be severely overrepresented in prison, making up over a quarter of all adults incarcerated. Indigenous children, less than 6 per cent of the population of 10-17 year-olds, are more than half of young Australians in detention.

In 2015, the NT Children’s Commissioner found that children in Don Dale Detention Centre had been placed in solitary confinement for between 6 and 17 days the year before. When a disturbance followed, they were hooded and tear gassed for up to eight minutes.

Australia continues to hold children as young as 10 and 11 in detention, even though the international standard is 12.

Tragically, at least five Indigenous people died in custody in 2015

“As a first step, Australia must set justice targets to end the over-representation of Indigenous people in prison. Australia can only hold its head high on the international stage when it listens to and works in partnership with its First Peoples to solve the crisis in Indigenous rights,” said Ms Mallinson.

Worldwide

Despite Australia’s efforts in 2014 to negotiate landmark UN Security Council resolutions aimed at protecting civilians in Syria, in 2015 the situation radically deteriorated. By the end of the year, 250,000 people had been killed; 7.6 million had become internally displaced and 4.6 million sought asylum abroad.

Governments from Saudi Arabia and Egypt to North Korea and China brutally silenced dissenting voices, and tortured and executed their citizens.

In China new laws were drafted or enacted that could be used to silence activists through expansive charges such as “inciting subversion”, “separatism” and “leaking state secrets” while in Malaysia tweeting and other forms of online expression led to arrests under the restrictive Sedition Act.

Australia pledged to campaign to end the death penalty, which was critically important, as the Asia Pacific carries out more executions than any other region. In Indonesia there were 14 executions in 2015, including those of Australians Andrew Chan and Myuran Sukumaran.

2015 did see many gains for human rights, such as the welcome release of Papuan prisoner of conscience Filep Karma, the Mongolian Parliament vote to end the death penalty, the people of Ireland voting for marriage equality and the UN General Assembly approving the Human Rights Defenders Resolution. These wins clearly show how people power combined with political will can and does create a force for change and protection of human rights.

Change is possible when governments put human rights first. Amnesty International is urging all UN member states to elect a strong, independent United Nations Secretary General, who will lead global action to protect and defend human rights.

The world today is facing many challenges, with refugees suffering in their millions. The world’s leaders have the power to prevent these crises spiraling further out of control, and decisive action is needed now to halt the assault on human rights.