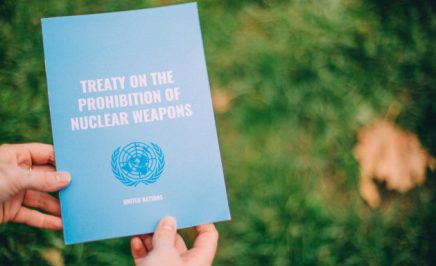

20 years of Amnesty International campaigning culminate in an Arms Trade Treaty that will protect human rights and potentially save millions of lives.

Let’s face it, the United Nations’ multilateral treaty process isn’t the most engaging nor is the treaty easily understood, so this week we wanted to give you a simple breakdown of what the treaty is and what it will mean for human rights.

What is “a multilateral Treaty”?

A multilateral treaty is an agreement between multiple countries about what they will and will not do when trading conventional weapons.

What do you mean when you say “we’ve achieved an Arms Trade Treaty”?

When people talk about achieving an Arms Trade Treaty they are referring to the UN General Assembly (sort of like the UN’s parliament) voting in favour of establishing the treaty. This happened last week with 155 yes votes, 3 no votes and 22 abstentions (not casting a vote either way).

So have all of those countries who voted “yes” signed the Treaty?

The treaty will open for signature after it has been deposited with the UN Secretary General in approximately one month.

All the countries that voted yes will not necessarily sign the treaty (though we hope they do). Countries like the US voted yes as a result of an executive decision by the President but may not sign the treaty because they need Senate approval that may not be forthcoming.

Many argue that this will make the treaty weak. It would undoubtedly be strengthened by key arms exporters like the US coming on board, but as we can see below there are a number of aspects to the treaty that will help save lives.

What’s in the treaty?

The Arms Trade Treaty contains 28 Articles and a preamble that outlines the new rules of the treaty.

You can read the full treaty here, but today we are only going to look at some of the key articles.

The scope

Articles 2, 3, and 4 outline what sorts of weapons the treaty covers, including battle tanks, attack helicopters, small and light weapons amongst others generally referred to as ‘conventional weapons’. Articles 3 and 4 ensure that ammunition and parts used with the conventional weapons listed in Article 2 are also covered by the treaty (this was a big topic of discussion during negotiations).

This treaty doesn’t cover landmines, cluster bombs or chemical weapons as there are separate international treaties for these types of weapons.

Prohibited transfers of weapons

Article 6 prohibits countries from transferring weapons if they know that the weapons would be used to commit genocide, crimes against humanity or war crimes at the time of transfer. (See Part 2, Articles 7 and 8 of the Rome Statute for definitions).

Practically this means that less weapons will end up in the hands of governments that have used them to commit war crimes or crimes against humanity. This prohibition will undoubtedly save thousand thousands of lives.

Export assessment

If an export of weapons isn’t prohibited under Article 6 (above) then Article 7 requires that governments assess the potential for weapons that are being transferred to commit serious human rights abuses and serious abuses of international humanitarian law (amongst other factors).

These abuses could include targeting civilians, torture, gender based violence, war crimes, crimes against humanity or genocide to name a few.

If there is a risk of abuse, then exporting countries must mitigate this risk. If there is an overriding risk then they must not authorize the transfer.

Just think of the impact this clause could have if a country knows that there is a risk that weapons will end up in the hands of child soldiers. Where there is a high risk that weapons could be used for war crimes, crimes against humanity or genocide, a country will not be allowed to authorize the transfer of weapons.

When does the Treaty take effect?

While the United Nations General Assembly has adopted this treaty, it will go to the Secretary General’s office to be opened for ratification. What this means is that individual governments will need to sign onto the treaty separately.

This is a reasonably lengthy process for countries to go through. Each country needs to follow its own processes of ratification (such as getting Senate approval in the US or Parliament pass legislation in Australia) and then lodge its ratification documents with the Secretary General.

This treaty will come into force three months after the 50th country ratifies (signs and lodges its paperwork with the UN Secretary General).

Amnesty lobbyists are preparing to pressure countries to ratify the treaty now and we are hopeful for the minimum number of ratifications over the coming months.

What happens when someone breaks the rules?

International law and treaties rely on the voluntary participation of countries. This treaty, like other international human rights instruments, will need to be enforced by you – by ordinary people holding governments to account.

Observing and responding when a transfer goes wrong or when abuses are committed will help to ensure that countries fulfill their treaty obligations. Similarly, organisations like Amnesty will continue to apply pressure in the same way — and where peace and security are threatened, the UN Security Council may intervene.

Article 14 outlines that countries must implement the Treaty in its national laws, but there is no enforcement mechanism if they do not.

Article 19 outlines that where a dispute exists between two countries (after negotiations, mediation, and conciliation) it can be referred for arbitration and decision.