The mother is everything – she is our consolation in sorrow, our hope in misery, and our strength in weakness. She is the source of love, mercy, sympathy, and forgiveness. He who loses his mother loses a pure soul who blesses and guards him constantly. – Khalil Gibran

Mums all over Australia sacrifice so much so that their kids can live their best lives. For #AussieMums who have traveled here from Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, Sierra Leone or Vietnam, those sacrifices include having to make dangerous journeys – not out of greed, or stupidity, but because they are fleeing harm and death with young families to protect and think of.

Many mums will spend Mother’s Day surrounded by their children, grandchildren and loved ones. However there are so many more that will not know if their children survived treacherous voyages across the Aegean or Mediterranean sea in seeking safety.

This Mother’s Day let’s pay our humblest of respects, gratitudes and thanks to #RefugeeMums all over the world who sacrifice so much of themselves for their children.

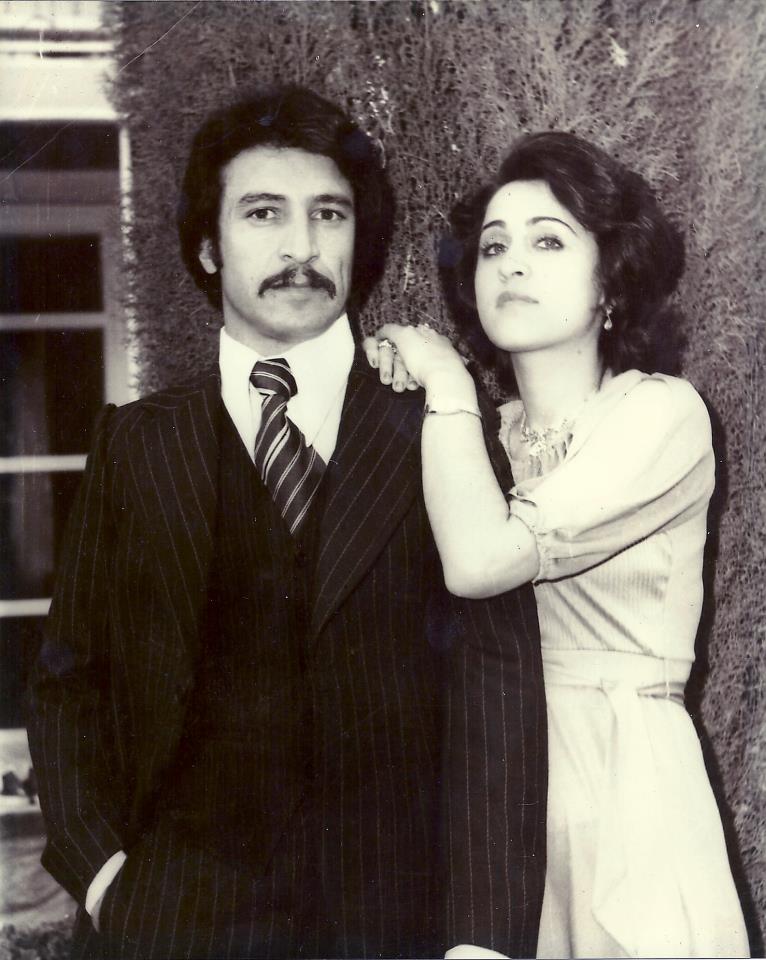

Zia Sayed

As a refugee from Afghanistan, we fled our home in Herat for the capital of Kabul because the Socialist regime installed in Afghanistan after the Soviet invasion was disappearing dissidents. We feared for my husband, who was a Doctor with the police. Our eldest daughter was 3 years old and I was 8 months pregnant with our youngest daughter when we were forced to leave.

We got fake passports to travel by air to India. Having small children, we couldn’t risk paying smugglers to get us out of the country, or traveling by foot through the Hindu Kush mountains. This was nearly 35 years ago now, and the situation for Afghans hasn’t improved at all. We were the lucky ones who got out early, but it was a close call.

My baby girl was born in India, and was 6 months old by the time we arrived in Australia. My earliest memory here was going to English courses while balancing motherhood. I had to discontinue the course, because the daycare wouldn’t accept children under 1 years old, and I got told that I should prioritise my child rather than studying English. I will never forget how overwhelmed and upset I was that the option of bettering myself was no longer available to me. We had lost our entire extended family network. We were alone and trying to find our way, and now this door was closed to me too.

I knew when we left Afghanistan that I might never see my father again – and I never did. When you leave your entire life behind, you have to face that reality. I was a primary school teacher and had to give up my career. We left our house and everything we had accumulated as newlyweds at that stage of our lives. We just wanted to live, so none of the material stuff mattered.

Without knowing the language when we arrived in Australia, not knowing our way around, alone and without much family around we forged our way. We went on to buy multiple businesses, hire Australian and other Afghan staff, sponsor other Afghan families to come to Australia; 30-40 in total, who went on to sponsor more to come to Australia.

From day 1 we were on a journey to improve ourselves and contribute to Australian society. We worked 7 days a week and didn’t take vacations so that we could give our children the best life possible. We had all the opportunities in the world and we have been very grateful.

I am very proud of my two daughters – my eldest is in pharmaceutical sales and my youngest is an international human rights lawyer, now working at Amnesty and contributing back. We had another child who was born in Perth, a son this time, and they have gone on to be an inspiring writer going off to do their Masters Degree in the US. We built our dream home in Perth and live a life we are very proud of.

Nalini Kasynathan

My family and I came to Australia in 1987. Even back then, it was not easy for people to come to Australia. We were lucky to be sponsored. We came with the clothes we had, and next to no savings. We spent it all to get here.

Things were difficult for us back in Sri Lanka. I still have memories of hiding my children in the attic of a neighbour’s house. The homes of our Tamil neighbours were burnt. Many Tamils were killed or assaulted, and we were lucky not to have been among them. This is why we left. Otherwise we would still be there, happily.

It was very hard for my husband and I to accept help from the individuals and organisations who helped us when we moved to Australia. We had never asked for anything in our lives. So it was a humbling experience to be desperate for the basics – clothes for our children, books for their schooling, and even food to eat. It was an experience I would not wish on anyone, and as grateful as we were for the assistance, it was emotionally very hard to accept that life had changed so dramatically.

Both my husband and I loved our lives as academics. We raised our children in a beautiful town where our university was. We have embraced life here in Australia, but life has never been quite the same.

I worked in the aid and development sector for much of my life – I was with Oxfam Australia for almost 30 years, where I was a gender specialist. Women’s empowerment and rights became the main focus of my work at Oxfam. This work was very important to me and I am glad to have done it. I am retired now, and looking after my grandkids.

Each of my four children have chosen careers that are focused not on making money, but on helping others. Our children haven’t forgotten where they come from or how we came here, and they have dedicated their lives to fairness, public service and social justice. It makes me happy to know that they are good people, doing good things… although the youngest one, he’s a bit of a trouble maker.

Khadija Gbla

I was born in Sierra Leone, west of Africa, where there was a civil war in 1990-91. My grandfather was politically active, so my family was a target and we had to flee as refugees. We traveled to Gambia and there was no refugee camp there, so we stayed for three years. We applied for refugee status through UNHCR and were granted visas to come to Australia in 2001. We have been in Australia ever since – 18 years now.

My first memory of Australia was that it was cold. I came from a tropical background, so it was a reality check to experience Adelaide in June! We had to adapt to not seeing people on the streets – it felt like a ghost town, and we wondered where all the people were. Supermarkets and snacks from the Asian grocer brought us comfort as we found similar foods to back home, and our first trip to the city was eye-opening. We noticed people looking at us a bit differently and they thought we were Sudanese, but we weren’t. The stereotyping was hard.

In Australia it hit home that we were now a minority. Being told to go back to where we came from was confronting. I missed living in a place where there was nothing wrong with my skin colour, my background or my home.

I missed out on knowing my grandfather, extended family and cousins. We came from a culture where extended family networks are so important, so being here with a nuclear family and not speaking the same language felt very isolating. Only having each other to rely on brought us closer, but it was still a constant struggle.

I miss being home and getting mentoring from older women, sharing our family history and cultural heritage. My fondest memories are of climbing trees, picking mangoes, running around and playing in Gambia. We had so much freedom, and the lack of sense of time is a very African trait that I still cherish. I miss the cultural nuance of hospitality, food, family and banding together. Having no access to TV and technology, everyone spent time together. The simple life was so free.

Motherhood has not slowed me down; I have made the system work for me. As an African-Australian woman I tell people who ask me to appear on panels or at events that my baby is coming – there is no stopping or slowing me down. This is what a modern African-Australian woman looks like. I chose the best parts of both of my cultures to feel empowered. I am not shy when I get a business opportunity. I make it work.

I didn’t feel welcome when I came to Australia, but this was my new home, so I had to make it my new home. No one else was going to do that for me. I took up volunteering as a way of understanding my new home and interacting outside my comfort zone. Understanding principles of a “fair go” and “mateship” made me feel like it was my home. I felt like I had so much to offer and there was finally space for me to share my experience and do advocacy to make social services more culturally appropriate for people like me.

I am nobody’s victim. I am a single Mum, doing it all and I am empowered. I want other women of colour to see someone in me who reflects them, so they are inspired too.

Having a beautiful child was a miracle, and motivated me even more to make this world a better place for him. I want him to know that his Mum is helping to make sure that every child and woman feels welcome here, and are safe and free from domestic violence and child abuse. Making sure that other people coming to Australia from non-English speaking backgrounds have equal access to services.

I want my son to see me as a feminist. I want him to know that women are equal and that he needs to be an ally. I want him to see me living a life that is fulfilled, and impacting the world that is bigger than me. I refuse to accept toxic masculinity in my home, and it starts with me and my son.

Loan Mai

After the Vietnam war, my family was persecuted because my Dad was an officer in the army. It was difficult to get an education, so at 13 years old I learnt to sew, made hats of bamboo and worked in a factory. I was married in 1981, and in 1982 – when I was 6 months pregnant with my son, Anh – we traveled to Indonesia by boat. It took us 4 days and 5 nights. I was so unwell and could barely eat.

In July, Anh was born. Life was hard in Indonesia. We had little opportunity, but we wanted to give our children a better opportunity than to work on farms with cows.

In 1983, we paid 3 ounces of gold per person to get out of Vietnam to Indonesia. We applied to be accepted as refugees to Australia while we were in Indonesia and we were accepted, so from there we traveled by plane to Australia.

In Indonesia we were so scared, but in Australia we were so happy. It was so spacious and safe here, but learning English was difficult and we had no money. I risked life and death to come to Australia, but I missed feeling connected with my country.

I found a sewing machine at the Midway market, and started making garments for the Vietnamese community. I really wanted to be a designer, but I had to sew to make a living, feed and educate my son, and send money to my family in Vietnam. I am a divorced, single Mum who has worked hard over the years on little sleep.

I tried my best to be a hard worker. The only time I have ever accepted benefits was when I was just divorced. I want to contribute to this country that has helped me and my family so much. I hope I’ve taught my kids a sense of responsibility to help out.

One of my proudest moments as a mum was at my son’s 21st birthday party. I got a thank-you speech in Vietnamese acknowledging everything – I want to see the video again!

Seeing my children go through high school and university and seeing all their successes is so affirming for me as a single Mum. There was so much negativity in the community when I got divorced, and an idea that my children would grow up naughty. I’m proud to have proven them all wrong.

Thank you to Australia for the opportunity. They have been nice, kind and generous in allowing me and my kids to grow up in a safe and well-educated society.