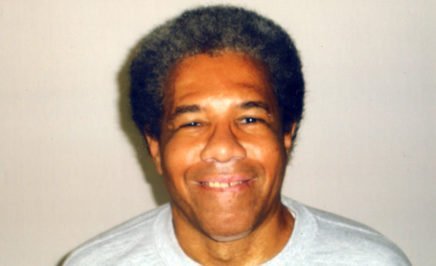

In 1974, at the age of 30, Herman Wallace was convicted of murder and imprisoned in solitary confinement at Louisiana State Penitentiary where he would spend the next 41 years.

His conviction was overturned in late September 2013 after it was ruled unconstitutional on the grounds that there was a “systematic exclusion of women” on the jury that indicted him.

Wallace passed away on 4 October 2013, just three days after his release. He was 71 years old.

Put yourself in his shoes

I turned 30 this year.

To me, 71 seems like light years away. 41 and a half years of living, with everything that this entails. I’ve never been big into planning, and trying to imagine what might happen in my life over the course of the next four decades is like trying, as a child, to imagine the blankness of eternity or the extent of the solar system.

Add to that the prospect of living those 15,000 days – give or take – alone in one room, with few distractions and no company, and I get one almighty headache.

Isolation

Picturing Herman as a young man, locked in a featureless, windowless 6-by-9-feet cell for 23 hours a day with no real human contact is difficult. I wonder how he felt each morning, waking from the oblivion of sleep to another day identical to all others. Once the fuss of his trial and subsequent appeals died down, how did he reconcile himself with the fact that isolation was now his life?

Weak evidence

Wallace was convicted, along with his friend Albert Woodfox, for the murder of prison guard Brent Miller. The two always maintained their innocence. In addition to a seemingly unfair trial by the Louisiana courts, the evidence against them was also weak, with no fingerprints belonging to the pair found at the scene.

What must it be like to watch yourself grow old in solitary confinement? And what if you were innocent? Looking down at your ageing hands and wondering what you would have used them for if things had been different. After how many years do you give up?

The Box

Solitary confinement – often referred to as ‘The box’ – can ruin a person in a matter of weeks, even days. Sometimes the damage is immediate and irreversible. Side effects can include panic, depression and even a nervous breakdown. It’s a wonder Wallace managed to hold onto his dignity – let alone his sanity.

Many people have faced – and still face – solitary confinement, and many are unable to cope with it the way Wallace did.

How did he do it? Well, for one, he kept busy. And he improvised.

To stay in shape, Wallace lifted weights made out of old newspapers. He read anything and everything and maintained a healthy interest in current affairs. Even locked up for 23 hours a day, the changing world beyond his cell didn’t pass Wallace by.

Perhaps most importantly, he never gave up hope. He replied to letters, worked on his appeal and continued to dream about life outside prison. He even took part in a documentary film called ‘Herman’s House’ in which an artist helped him create a dream house he hoped to live in someday.

Basically, he didn’t give up. He survived. He stuck it to an inhumane system that torments individuals for as long as possible.

Staying sane

Many people have faced – and still face – solitary confinement, and many are unable to cope with it the way Wallace did.

How did he do it? Well, for one, he kept busy. And he improvised.

To stay in shape, Wallace lifted weight made out of old newspapers. He read anything and everything and maintained a healthy interest in current affairs. Even locked up for 23 hours a day, the changing world beyond his cell didn’t pass Wallace by.

Perhaps most importantly, he never gave up hope. He replied to letters, worked on his appeal and continued to dream about life outside prison. He even took part in a documentary film called ‘Herman’s House’ in which an artist helped him create a dream house he hoped to live in someday.

Basically, he didn’t give up. He survived. He stuck it to an inhumane system designed to torment him for as long as possible and then tear him down to nothing.

Cruel and unusual

For me, it’s clear cut. Solitary confinement, like the death penalty and torture, is wrong. It’s cruel and it’s unusual. And it’s a common practice around the world.

Data revealed by a Bureau of Justice Statistics census in 2005 shows, at that time, 81,000 people were being held in solitary confinement in the US alone. The worldwide figure must be sky high.

Hope

In many ways, although his life’s trajectory was ultimately a sad one – compounded by the cruel irony of his death so soon after gaining freedom – Herman Wallace represents strength and hope. He showed us that the human spirit, though fallible, is tough to break.

His final words were not ones of hatred, revenge or self-pity; he simply said ‘I’m free, I’m free’.

Article written by Katie Young, Online Editor