To read or listen to the headlines in Queensland at the moment, you’d be surprised people were game enough to leave their houses for the youth crime emergency. Last week’s announcement of the highly visible police patrols are the latest in the knee-jerk responses to deeply complex problems.

Let’s not forget when we’re talking about the people affected in the name of the Safer Communities Bill – due to go before Queensland Parliament this week – what we are actually talking about is targeting children as young as 10 because it’s them, and mostly First Nations kids, who are going to bear the brunt of this.

The issue isn’t new, and the government knows that there are more effective ways to deal with the issues.

In 2018 the Atkinson report, commissioned by the Palaszczuk government into youth justice, found that public safety would be best served by adopting the following four pillars in dealing with youth offending:

- Intervene early

- Keep children out of court

- Keep children out of custody

- Reduce reoffending.

Pleasingly, the Queensland government accepted Bob Atkinson’s recommendations in full.

Well, they said they did.

What they actually did was plough an initial $320m into building new youth detention centres. By comparison, a paltry $1.3 million was set aside in the 2021-22 budget for the continuation of the transitional hub in Mount Isa (one of the so-called youth justice hot spots) on a diversion program providing a therapeutic environment for police to refer young people who do not have appropriate accommodation or safe home environments.

It’s hard not to interpret this as sacrificing the welfare of vulnerable kids for the sake of a more electorally palatable stance. All the evidence, and all the youth justice inquiries in all the states and territories in this country have come to the same conclusion: locking kids up doesn’t stop offending, doesn’t make the community safer and more alarmingly it damages kids who, if diverted toward therapeutic programs would be almost certain to go on to lead healthy and happy lives free of the criminal justice system.

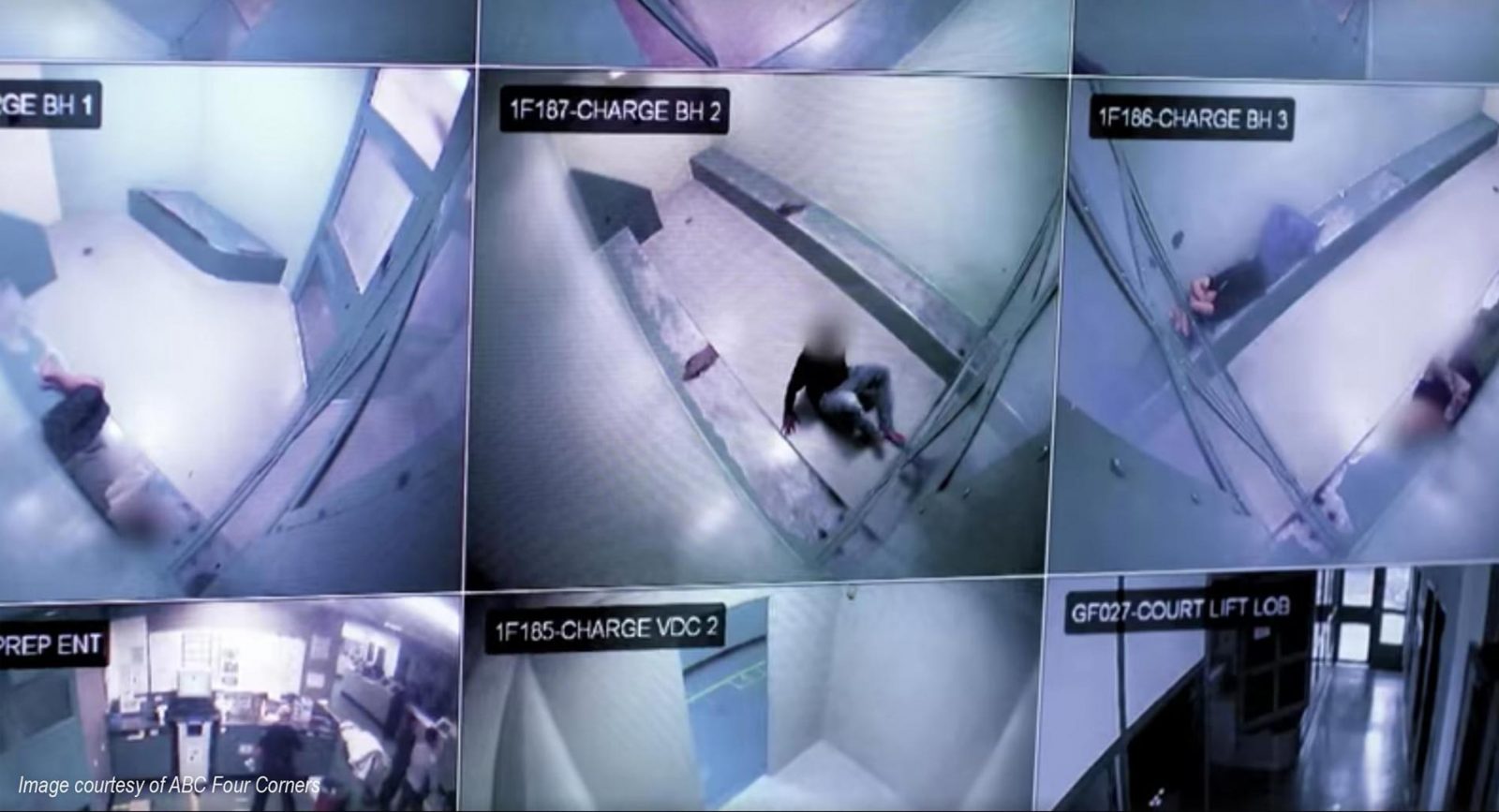

After the revelations Four Corners aired in 2019 based on Amnesty’s own FOI requests of children being held in maximum security watch houses, the government again responded with concerned platitudes and a massive injection of money into doing the same thing and expecting a different outcome.

However, the latest move by the Queensland government to overturn its own human rights act (ironically just as the Human Rights Commission launches its model for a federal act) to criminalise breach of bail for children plumbs new depths of desperation to be seen to be acting, but in reality further harming the kids who need the most help. Even the state’s own Police Minister Mark Ryan admits “that these provisions are incompatible with human rights”.

Attempting to overturn the human rights act suggests that human rights are conditional. When in actuality, everyone is entitled to their human rights, no one is more or less worthy of protection.

And yet, we’re watching a government say just that. A vulnerable and disenfranchised group is electorally expendable, if not morally.

And let’s not forget the rather large elephant in the room: racism. Queensland’s own Human Rights Commissioner Scott McDougall told ABC radio this new Bill will affect First Nations kids disproportionately as they make up the largest percentage of kids in detention.

Queensland’s 2019-2023 strategy on youth justice reforms promised to reduce offending, reoffending, remand and detention of young people and the over-representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. Last year, Youth Justice Minister Leanne Linard ruled out making breach of bail a crime, citing its ineffectiveness in reducing crime. And yet here we are with the government citing an emergency to breach its own Human Rights Act.

The real emergency here is what we are prepared to do to little kids in the name of votes.

Only $4 million of an additional $332 million as part of the youth justice strategy is for on-country programs for First Nations communities. This allocation is dwarfed by spending on other programs, such as $66 million allocated for “proactive policing” including high-visibility police patrols announced yesterday.

Mounting evidence has shown that over-policing does not keep children out of prison. But community-led prevention and early intervention programs do. Violent actions or behaviour in young children, especially Aboriginal children, are often directly linked to experiences of intergenerational trauma resulting from colonisation and racism and unresolved mental or physical health problems.

Government systems dealing with child protection and youth justice have repeatedly failed Aboriginal families. There are many examples of successful community-led solutions across the country. They need proper, long-term funding and a commitment from the Government to move away from Band-Aid responses that harm kids and don’t achieve the outcomes they promise.

When are we going to see our lawmakers do what we need them to do – invest in programs that work, not in populist knee-jerk action where everyone loses out.

Kacey Teerman is Amnesty International Australia’s Indigenous Rights campaigner