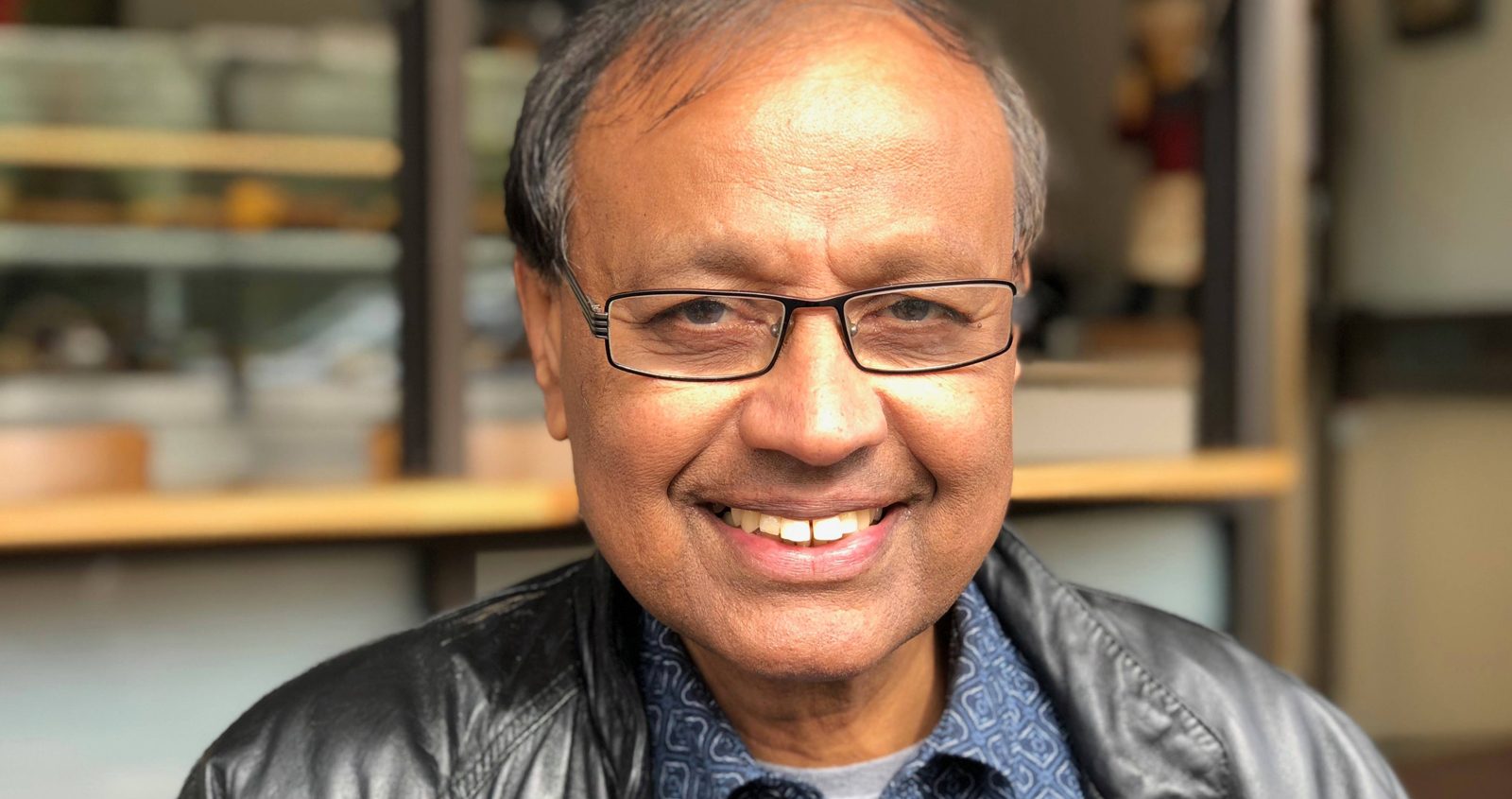

Reverend John Jegasothy and his family sought safety in Australia, after fleeing Sri Lanka’s civil war. Today he is a community leader in Sydney helping to promote a fair go for refugees. Story as told to Annika Flensburg.

Fleeing Sri Lanka

When Sri Lanka’s civil war started, I was working as a Superintendent Minister in the Methodist Church; I also chaired a human rights organisation branch in Trincomalee and was a Central Committee member.

I invited local leaders and heads of all forces to peace talks, and I became the voice of the Tamils – I said that there is no reconciliation without saying sorry. It was then that I became a target. Messages came to me that, if I slept in the house or came to the market place, they would cut my throat.

In Chenkaladi, my next church, on a hot Independence Day the Sri Lankan Task Force (STF) Commander came to our premises and asked for water. It was unusual. While he was talking a soldier next to him fired his AK47 into the lane alongside our house. We were carrying our two children in our hands and they were very frightened and screamed. Then the soldiers went out to the road and shot a young boy they had arrested.

An offer of sponsorship

Soon after our 10-month-old son Edward had convulsions and a high fever. My wife, the nanny and I ran to a doctor’s house – there was a curfew outside and it was very dangerous; either side could have shot us. The doctor said that we needed to take Edward to hospital.

“We put up a nappy as a white flag on our car and went 10 miles, risking our lives.”

Edward woke up at the hospital and today he is a lecturer at Sydney University.

When I came back home that night to look after my older son James, the first thing I saw on the table was a letter of sponsorship from Shanti’s younger sister in Canberra. At the time the Australian authorities were granting humanitarian visas to Tamils in danger if they had someone to sponsor.

The letter was sent a long time ago but I’d never read it. Now it was staring at me. I filled in all the papers. When Shanti came home with Edward she sent it to the Australian embassy before I could change my mind. We didn’t want our children to die before us.

A new start

I remember sitting on the plane after being granted a permanent visa still worried that the authorities would call my name and force me off because of my human rights and humanitarian work. I also felt sad and guilty for leaving my people. It was very hard.

We arrived in Canberra in 1986 and I was accepted into The Uniting Church as a minister.

Soon we were invited to the regional New South Wales town of Parkes where I began my ministry in Australia. It was predominantly a white Australian community and I was the first minister with dark skin and from an unknown culture, so in a way it was a new start for everyone.

“People in country towns are famous for ‘dry jokes’, which I couldn’t understand fully!”

I remember once in a Rotary meeting, the community members asked me to lead the singing. I said I was “happy to add colour to any situation”. From that day they didn’t hesitate to crack jokes with me and we became just mates.

Finding belonging

Most importantly, we wanted the other kids to be accepting of our children. In the beginning someone at school called our children black. I told them to say that they were brown like chocolate, which everyone likes. That broke the ice; everyone loved the boys at school.

The community needed a catalyst and I think I became that person. The church became full, people who hadn’t come for a long time started to come. We undertook so many initiatives, including an Annual Church Fete where hundreds of people came, and also a successful art and craft exhibition.

We felt we belonged to this country. People invited us to their homes and farms, saying their doors were always open.

Sanctuary and life

I came to Sydney in 1996 as a minister of the Uniting Church. An asylum seeker, Leonard, asked me to the Villawood Detention Centre in Sydney.

“When I went to see him I saw all the shortcomings in the detention centre and started speaking up for fairer treatment.”

The government started giving Temporary Protection Visas from 1999 to refugees and didn’t assist sufficiently in settlement, so we opened up our home. Many refugees have passed through our house. We helped them to open bank accounts, Medicare, find work, networks. I became their case worker, confidant, social worker and ‘father’.

Welcoming communities

In order for people to settle into their new environments and find safety, mental health and peace, our politicians need to stop playing political football with asylum seekers.

“Australia is a compassionate country.”

If we are going to be truly human we have to think in terms of one humanity and we should be able to provide sanctuary and a new life for these vulnerable people.

I think it is good if newcomers and refugees move to regional areas that are ready to welcome them. Not just churches, but all types of groups can welcome new people – sports groups like cricket and soccer. As organisations, they could sponsor refugees to come here, and they could make significant contributions and maybe they’ll make good players too! In fact recent asylum seekers formed the ‘Ocean’s 12’ cricket team with the help of the Blue Mountains Refugee Group, and became national champions.

No doubt it’s going to be a different Australia altogether when we welcome new talents and skills into the country.