As someone born to stateless parents, and who has been stateless all my life, I found it impossible to imagine a life of freedom, respect, opportunities and love. It is a life I thought I would never experience.

I fled Myanmar (Burma) when I was 16, boarding many boats to seek a country I could call my own. I passed through Bangladesh, Malaysia, Indonesia, Australia and Papua New Guinea – it was nearly seven years to be free. With my status as a refugee recognised, I tried to claim asylum in Australia. However, Australia imprisoned me on Manus Island for four and a half years, until I was released in 2018.

I have never understood why we have to go through obstacles and pain in our lives. I didn’t want to be stateless; I didn’t ask to face traumatic events; I didn’t want to have to get on boats to cross many borders; I didn’t want to put myself in life-or-death situations. All I wanted was to have a roof over my head and live a safe life with my family. These are very basic human rights that millions of refugees can’t even imagine having.

“My world has been so dark since the day I was born, although I have done no wrong.”

There are thousands of Rohingya people who will never get the chance to say that they are safe and free. Rohingya are the indigenous ethnic minority of Myanmar, mainly living in Arakan (Rakhine) State. Outside Myanmar, the Rohingya population is approximately four million. Of this diaspora, more than 2.5 million were forced to flee, and are now in Bangladesh, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Malaysia, India, Thailand, Indonesia and other countries.

Rohingya are considered the most persecuted minority in the world. They are made stateless in their own ancestral land, denied citizenship and subjected to decade long systematic persecution.They die on their own land, as well as foreign lands, without knowing that there is a world where they can live in safety with opportunity, love and respect.

I am one of the lucky ones. In 2018, I was freed from Australia’s offshore prison on Manus Island. The day I arrived in Chicago was the day I consider myself reborn. I didn’t have my mother beside me to guide me and everything was so new, scary and overwhelming. I got lost four times in the early weeks, unable to find my apartment because all the buildings looked the same and all the roads were packed with cars. One night I was lost and my phone was flat – I didn’t know what to do. I was so hopeless until I saw the Iraqi woman who lived on the other side of the road. It was then that I realised I was standing right in front of my apartment.

Settling in Chicago hasn’t been easy. There are hundreds of things I have never been exposed to before, that other people take for granted. I feel like people expect me to function like they do in their everyday life, as though I too have been here for years. I am trying my best to move with positivity so I can use my life for good and be a voice for others. I feel blessed to be able to read, write and speak English. I have been asked how I learned English without any schooling or materials. And to be honest, I don’t really know – what I do know, is that I am very motivated and driven.

“I didn’t know how to write a complete sentence in English when I was forcibly taken to Manus Island by the Australian government. It was easy to become extremely depressed, but I didn’t let that torturous setting control my brain.”

We had a couple of teachers in the camp and I never missed a chance to speak to them. One of the teachers told me to write something everyday, so I did. One of the case-workers was kind enough to risk her job to get me papers and pencils. Case workers were not allowed to give detainees these things.I wrote by sitting on the concrete floor on a piece of cardboard all day and night, surrounded by hundreds of refugees playing cards and security guards laughing and talking loudly. I chased the case workers, teachers, security guards and everyone who spoke English, to improve my understanding of the language. I taught my friends while I was learning. I wrote almost 14 hours a day, even forgetting to eat from time to time.

Writing provided a purpose to every single day, and helped me keep my sanity. I reached out to people from around the world, coordinating with many Australian journalists, lawyers and advocates on articles. I started writing my own articles and they have been published around the world. I finished writing my autobiography while I was incarcerated. I haven’t published it yet, because I want to write one more chapter about my freedom.

“I felt like I was given the whole world in my hands when I received my state ID, social security card and employment card – I have waited my whole life to have these documents.”

I am doing my best to work towards the future I have dreamed of all these years. I believe education is the key to everything, and no one can take it away from me. I am studying full time now for my high school diploma at Truman College in Chicago. It is a dream that will never come true for millions of Rohingya.

I wish my family was here – it would be so much easier for me to grow and develop in my life. However, the people of Chicago have been so welcoming. I don’t know how to thank everyone for thinking of me and inviting me to their homes, and to join them for meals. Their invitations have filled my heart with so much love. I feel blessed to have people around me who generously show love and kindness. I have told my mother everything about my life here, and she knows that I am loved enormously in my new country.

I came from a country with so many problems. Even though there are a few difficulties here in the US, my life is good now. I am safe and will keep working to build the life I have dreamed of. I will accomplish my goals through all of the love and support I am receiving. I will be forever grateful to this nation for the life I have been given, and I will continue to hope that the world will be kind to the millions of refugees who are suffering unbearably around the world.

As long as there are humans who are genuinely trying to save others in the world, there is hope. It is our responsibility as people to help others and I hope this will continue to happen.

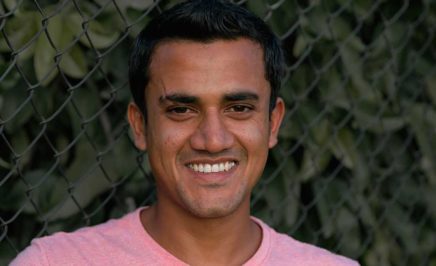

Imran Mohammad is a Rohingya refugee who was held on Manus Island for more than four years. He learnt English while in detention.